World day of π

The Number π

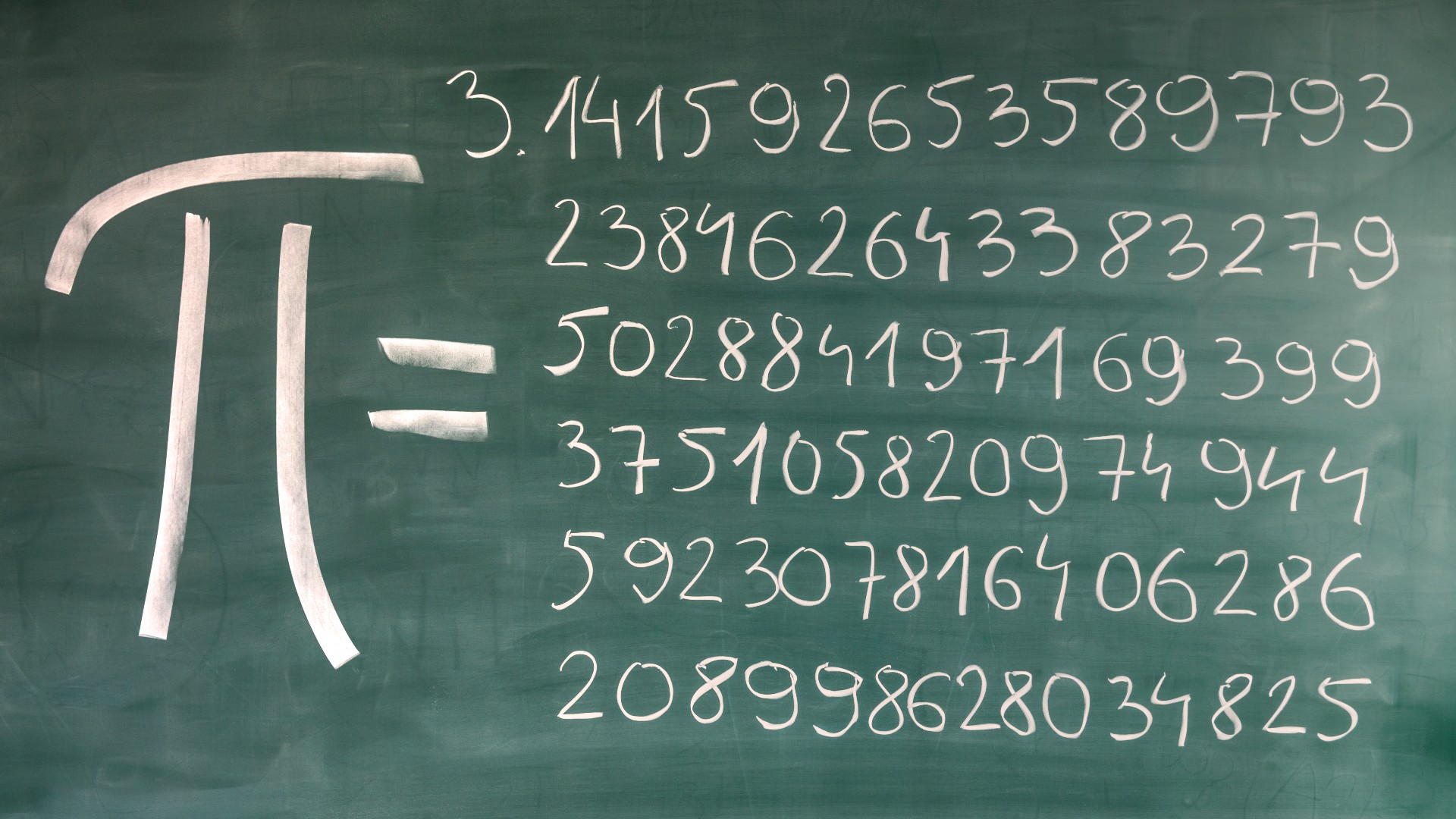

The number π (symbolized internationally by the Greek letter π) is a mathematical constant defined as the ratio of the circumference to the diameter of a circle, and is equal to 3.14159265 to eight decimal places. It has been expressed with the Greek letter π since the middle of the 18th century. π is an irrational number, meaning that it cannot be expressed exactly as a ratio of two integers (such as 22/7 or other fractions commonly used to approximate π). Therefore, the decimal representation never ends and never settles in a permanent and recurring pattern. π is a transcendental number – that is, it is not a root of a non-zero polynomial with exponential coefficients.

World π Day Celebration

World π Day is not exclusively for mathematicians and is celebrated every year on March 14th because of some numerical coincidences that occur on that day. In America, for example, 14/3 is written as 3-14, which is the value of the constant (π = 3.14).

The celebration of “p” day was established in 1988 by Larry Shaw in San Francisco. It is celebrated with the consumption of round pies because in English, the Greek letter π resembles the English word “pie” which is pronounced as “pie”.

The Story of π

When the ancient Babylonians began to build the city - says the legend - they were particularly concerned with geometry. Already from the 20th century BCE, they found that when the circumference of any circle is divided by its diameter, the result is always about three. They even calculated the value of this ratio at 25/8, which is only 0.5% of its true value. Much less accurate is the other of the most ancient values of π, which we find in the Bible (1 Kings, 7, 23), according to which the circular lake of Solomon’s house had a diameter of ten cubits and a circumference of thirty cubits, placing the value exactly at three.

One of the oldest and most accurate values is that of the Egyptian scribe Ahmes. He recorded it in a papyrus of the Middle Kingdom, around 1650 BCE, essentially copying an even more ancient papyrus. Ahmes described π as the result of dividing 256 by 81, i.e., 3.160.

But the one who is considered to have been the first to approach the calculation of π on a more theoretical basis was Archimedes, which is why π is also known as Archimedes’ constant. Chinese, Indian, and Persian sages all tried to calculate this constant. However, the name we know it by today was given to it in 1706, when the Welsh mathematician William Jones proposed that Archimedes’ constant be named after the Greek letter π, from the word “perimeter”.

However, the great difficulties with π had not yet begun. In 1761, Johann Lambert proved that π is an irrational number. In simple terms, this means that it cannot be expressed as a fraction of two whole numbers. In school, children learn that π is approximately 22/7, but this value is again approximate because π is beyond mathematical logic.

The second major breakthrough came in 1882, when Ferdinand von Lindemann proved that π had another unusual property: it was a transcendental number. In mathematical terms, this means that it is not the root of any algebraic equation with exponential coefficients.

In non-mathematical terms, this means that π is the proof of the old adage that one cannot square the circle. That is, one cannot, using only a ruler and a compass, make a square that has exactly the same area as a given circle.

But the elegance of the nature of π is summed up in the many efforts that have been and continue to be made to complete its numbers. The persistent search may have begun with the German mathematician Ludolph van Ceulen, who around 1600 calculated the first 35 decimal places of π. He was so proud of this work, to which he devoted much of his life, that he requested that the 35 digits be inscribed on his tombstone. Equally persistent, William Shanks, for his part, spent 20 years calculating, advancing π to 707 decimal places. Unfortunately, his achievement suffered a huge blow when the first digital computers discovered that he had made a mistake in the 528th decimal place, rendering all subsequent ones useless.

The expansion of π to infinity has also repeatedly attracted the interest of science fiction writers. The great American astronomer Carl Sagan, in his book “Contact,” hid the signature of the aliens in the supposedly random digits of π, which in fact do not follow any particular order.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: